Nordlight is a haven for travellers and readers at the edge of the World, between the snowy peaks of Vanna Island and the Barents Sea. Geography calls it a peninsula, with a windswept cape, a small bay prized by killer whales, and a tundra of rocks and grasses, sometimes white, sometimes green, fought over by gulls, woodcocks, terns, sheep and reindeer.

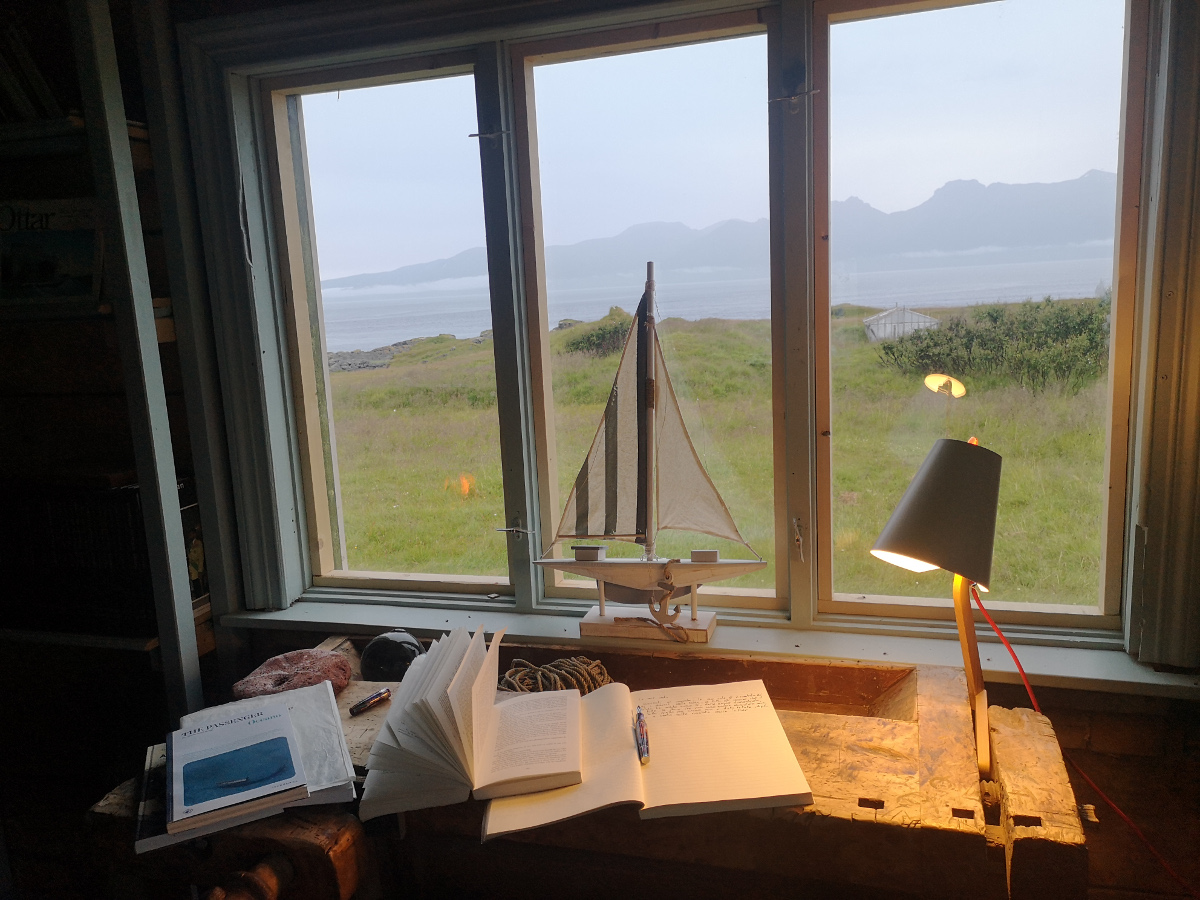

Nordlight’s white house, the House of Books, is now 101 years old and is all wood, nails and glass. The ground floor will become a library designed to tell the story of the Arctic and its people, a refuge for islanders, the curious and readers who want to come and discover it. It will be a house that tells its own story, and that of those who come to discover it. The door will always be open, like churches used to be. In churches a candle was lit, here a book is left behind. The library with its beams will house the travellers and creative people who want to go up here, and it will never be connected to the network.

The red house, the refuge for sea and mountain travellers, is half a century younger, but its four rooms and lounge are still made of wood, nails and glass. Its large windows open onto the Auroras, the ocean and the present of fibre optics.

Nordlight’s two houses are in the centre of the Keila peninsula, on a 15-hectare plot of land formerly used as a farm, with about a kilometre of private shoreline, and a lighthouse. We like to think of the centre of our activities as an event in space where time does not flow and nothing needs to be done, only to merge with the wind, the sea, the prairie, the snow and the rocks that surround us.

And always immersed in the poetry of light.

Every architectural element, from the design to the materials to the decroations, is the result of research to combine local tradition, use of island materials and reuse of traditional artefacts. Tables have been created from old doors, light has risen from old skis, old beds have been salvaged as far as possible, wood and beams have been brought into view, all types of plastic have been eliminated with the exception of old fishing buoys that have been salvaged from the beach and now serve as a colour element, and we try to use the best plates, cutlery and glasses collected by the old owner in his travels (he was a cook on the liners).

Our story

The snowflake does not ‘fall’, up here in the Arctic, but flies steadily with the incessant wind until a rock, a house, a ridge, a fence or whatever manages to stay upright in the gusts gives it a protected place for a break, whether short or long, it may end up embraced with millions of others in a small sheltered valley until spring, or a different wind will continue to write its story by whirling it towards stillness behind other rocks and other valleys, or perhaps under some terrace. So the snowpack can never be constant, it will be the geography of nature and sometimes even of men that will create a sea of waves, now high and soft breasts, now icy and eternal blades, but always with those shapes drawn by the storm, bold stripes of a furious sculptor who uses air instead of light to create his shapes and counters. Sculptures that the Russians call sastrugi, certainly not unfamiliar to those who run from bivouac to bivouac in the Alps, but which here start from the beach, from the door of the house, from the wheels of the car, from a thought that has lasted too long.

The nomadic, inquisitive soul does not ‘travel’ up here in the Arctic, but struggles constantly with the incessant wind until a harbour, a house, a tent, a boat or whatever manages to stay upright in the gusts grants him a protected place for a break, be it short or long, he may end up embraced with dozens of his fellow travellers in a small sheltered valley until the autumn of his existence, or a different wind will continue to write his story, whirling him towards the quiet promised by other islands, other hearths, other vistas, other winters, other loves. Thus the life of the nomad can never be constant, it will be the geography of nature and sometimes even of men that will write his story, now among soft and smooth breasts, now among icy and eternal blades, but always with those shapes drawn by destiny, bold stripes of a furious writer who uses air instead of light to create his stories and his dreams.

There is little difference between our life and that of a snowflake, we cannot choose where we fall and it will always be the wind of destiny that blows us between ridges and rocks, between loves and disasters, between harbours and homes. What we can do is to try or not try to attach ourselves to the world, be it a mouth or a place, or wait for the next gust and let it write our future.

Cadeau entered the harbour of Kristoffervalen on one of those plaid afternoons when you just hope to find a sheltered pier, and to find it quickly, and in such cases no solution is better than the side of another sailboat, the first one encountered in days. On the pier was a gentleman whose upper eyebrow suggested that curiosity mixed with veiled scepticism that often apostrophises the eyes of people from the north at the arrival of tourists, who here are all those arriving from the south, including Tromsø. And to the south is almost the whole world.

‘Good evening, do you know the mooring situation here? Do you think I can moor that boat?’

‘That boat is mine, and sure, I think it’s a good berth. But what are you doing here?’

‘I’m looking for a new home for me and a port for my boat’

If there is an elixir capable of evaporating all scepticism from the Norwegian soul, it is the sharing of dreams, and by the end of the second Tom Collins JH had fallen in love with my idea of creating a travellers’ haven at the end of the world.

Vannøya is a community of other spaces and other times, capable of circulating information at, precisely, relativistic speeds, and within a few days word spread that an Italian navigator was looking for the elsewhere of his dreams. After about ten days JH called me, inviting me to take a boat to the western end of the island and take a look at the land. I saw a series of houses hugging a beach and two more houses, further out, overlooking the cape. JH was immediately clear in declaring himself surprised that the white house was still standing after a hundred years, because that is one of the windiest capes in the area (80-90 knots are not uncommon in late winter) but, he added, if it is still there, there must be a reason. I lost the keys during my first steps in the snow, around the houses. After a few days the property accepted my offer and these are latitudes where words are final and down payments are not deemed necessary.

‘The area is actually known on the island as Toga. When there was no road, travellers between Vannvag and Kristoffervalen would stop here, where they knew they would find a warm place and coffee always ready,’ they explained to me in those days. A refuge. Voices told behind a café sheltered from the wind. A house that tells of an island and its people. Voices. Memories. Tales. Books. A house of stories and books at the end of the world.

Open.

Because elsewhere at the end of the world is too good for one person.